Search for books, articles, and more

Massive Four-Sheet Bamberg Wall Almanac

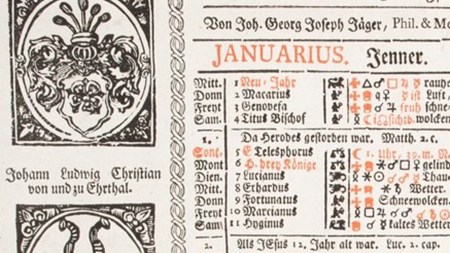

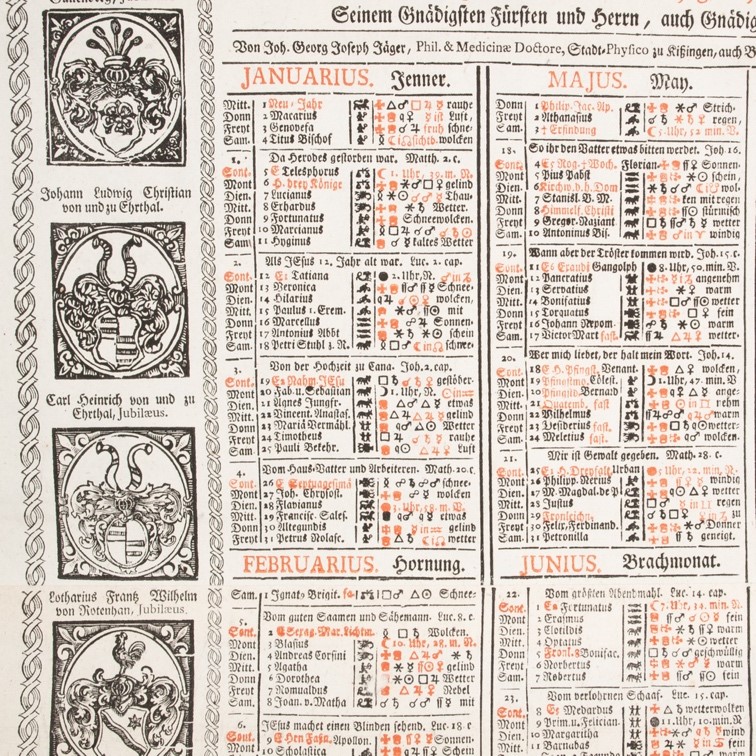

Jaeger, Johann Georg Joseph. Allmanach Bamberger bistums auf das dritte nach dem dreyzehenden schalt-jahr dieses saeculi nach der gnadenreichen geburt Jesu Christi MDCCLV. Bamberg: Georg Andreas Gertner [Anna Elisabeth Ida Gertner], [1754?]. 1 broadside, full-sheet.

Submitted for adoption by Earle Havens, PhD

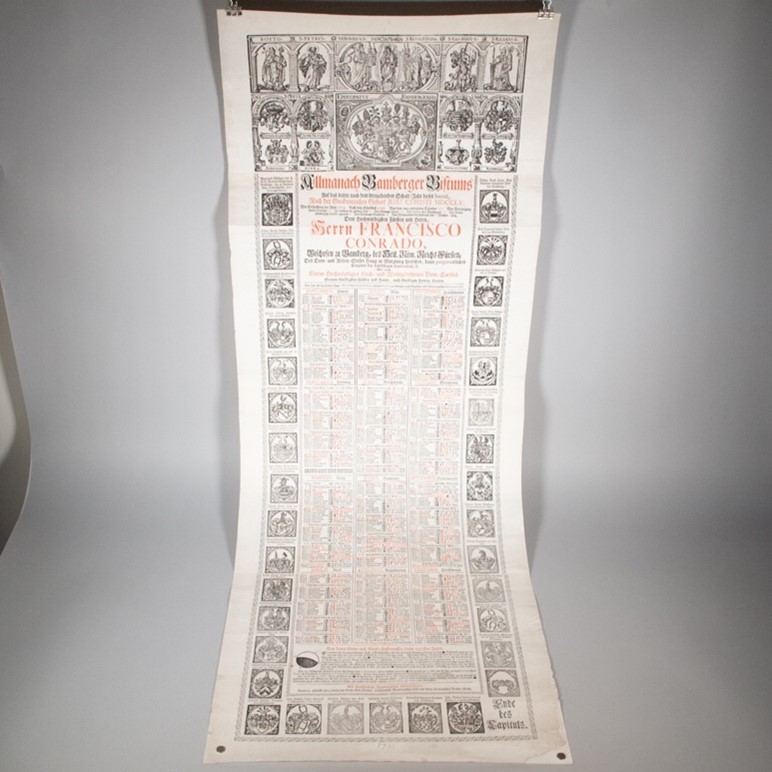

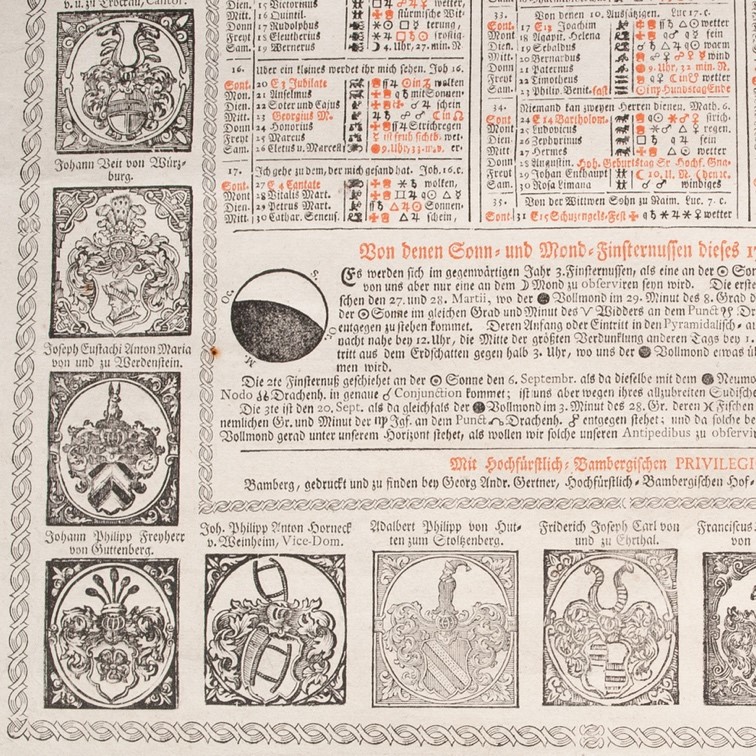

This enormous four-sheet broadside almanac was made around 1754 for the Bavarian Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg It is one in a long line of annual imprints going back at least as far as 1683, when the woodcut spanning the top of the present sheet—attributed to Nuremberg craftsman Johann Georg Lindstatt—was first used. Since the printer, Georg Andreas Gertner, had died three years prior to this publication in 1751, it is presumed that his widow, Anna Elisabeth Ida Gertner, was the actual printer.

This 1754 Bamberg almanac appears to be unique as no other copies are recorded. Institutional copies for the subsequent 1755 Bamberg almanac are found only at the Saatsbibliothek Bamberg (HVG 10/13) and the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich. Taking their ephemeral purpose with the obvious challenge of storing such large items in the long term, it can be suspected these prints are very rare.

This particular exemplar of the wall almanac reveals a kind of international fusion in its design. It combines the massive grandeur of the French wall calendars, popularized during the reign of Louis XIV in the 17th century, with the text arrangement of the German broadsheet almanac, characterized by numerous individual woodcuts surrounding a letterpress calendar.

The illustrations depart from the more traditional seasonal and biblical scenes of earlier examples. Instead, the arms of the powerful Prince Bishop Franz Konrad von Stadion und Thannhausen are centered at the top.

The illustrations depart from the more traditional seasonal and biblical scenes of earlier examples. Instead, the arms of the powerful Prince Bishop Franz Konrad von Stadion und Thannhausen are centered at the top.

The size, perhaps, is the most remarkable deviation of this almanac from its German ancestors.

While earlier 16th-century wall almanacs commonly used two sheets pasted together along the short edge, this one pastes together four sheets along the long edge, substantially boosting its dimensions along both axes.

Sources:

- Laure Beaumont-Maillet, Les effets du soleil: almanachs du règne de Louis XIV (1995), 7: “Jeopardized [fragilisées] by their large dimensions and by their ephemeral nature, tied to the calendar they accompanied, these prints have become very rare outside of public collections.”

- Miriam Usher Chrisman, Lay Culture, Learned Culture: Books and Social Change in Strasbourg, 1480-1599 (1982), 74: In 16th-century Strasbourg, wall calendars were found on the wall of a mine foreman’s widow, and in the office of an orphanage administrator.

- Maxine Préaud, “Introduction,” Effets du soleil, 12: On massive 17th-century French wall calendars: “Almanacs are found where they are useful, which is to say, among people who work…. They were probably in cabarets…affixed to partitions [cloisons], exposed to the light, to smoke, and to cooking grease of kitchens in a dirty and dusty city, these images had a hard time reaching the end of the year in good condition. And, when their replacements came, they were thrown away, used to wrap vegetables or to light the fire.”

- Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life (2011), 73: “At the heart of the need to locate oneself in time and space was the calendar, one of the many ways man organized time, and one of the first to be printed in the form of books or sheets to be hung on the wall.”

- Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (Brill, 2018), p. 254: The broadside format “would become extremely popular in the second half of the sixteenth century, with numerous versions designed by Jost Amman, among other artists…The down-to-earth occupations mentioned correspond with the status of their owners.”